Should you give that new restaurant around the corner a try, or instead play it safe and grab those snacks you love from one of your favorite places? This is an instance of a more general problem known as the explore/exploit tradeoff, which basically asks the question of when it is a good idea for someone to “exploit” the knowledge he has gained in the past and when to ignore that knowledge and go for something unknown or new. Going back to the restaurant scenario, the snacks you now love are, frequently, the result of a learning process that involved a fair amount of trial and error. So, the question the dilemma ask is if you should exploit that knowledge or explore novel alternatives.

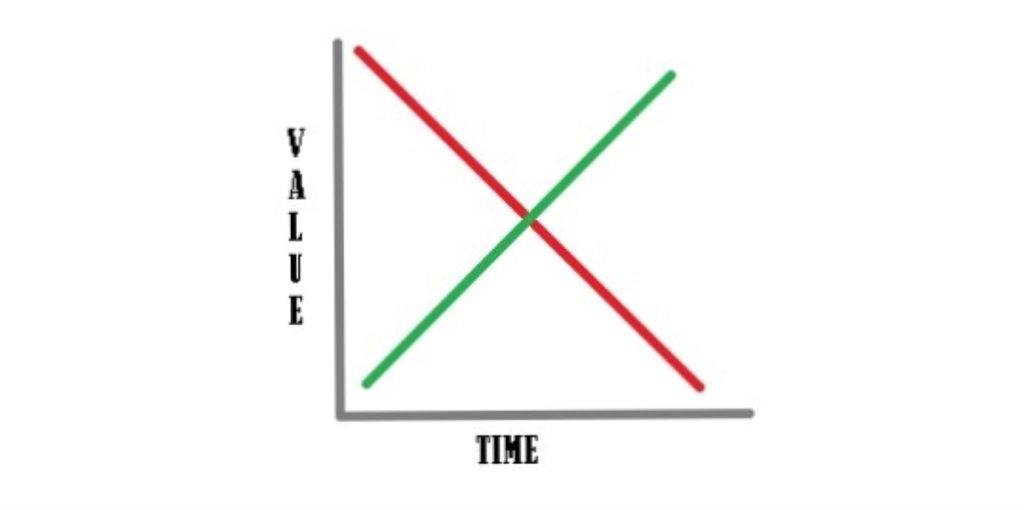

It turns out that if we want to optimize or, in other words, make a good decision, faced with the exploiting/exploring alternatives, there are a few guidelines we can rely on. First of all, exploring is valuable in itself. Some very conservative people believe that new things are inherently bad. There are even some bits of “wisdom” to convey the idea (“Better the Devil you know”). However, what these persons are missing is that the judgments they make inherently involve exploring. After all, there was some point in the past when you didn’t know the devil that you now do. In consequence, by default, exploration should be assigned some value. Secondly, take time into account. Basically, the takeaway here is that the value of exploring goes up the more time you have (while the value of exploiting does just the opposite). In the graph, the green line (sort of) specifies how the value of exploring changes with time while the red line does the same thing for exploiting.

Several things are worth noting about the line graph. Obviously, a context has to be specified. Even if the same general principles can be employed to arrive at decisions in many different life domains, time constraints will be different. Take the case of searching for a TV program on a weekday night vs doing it on a Sunday afternoon. If you are like most people, it is likely you have much more time to browse for a show on Sunday, and then jumping into watching the first thing that catches your eye would not be optimal; the same strategy on a weekday can be, on the other hand, your best bet. Secondly, domains vary greatly in terms of time demands. In Algorithms to Live By, Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths say that some of the challenges elderly people face in nursing homes and age care facilities is that they can barely exploit the value of friendships and other relationships they have built over the years. Elderly people are in a stage where exploring the personal relationships “market” does not make a lot of sense because creating deep relationships frequently requires a lot of time (we’re talking about years or, in the best case scenarios, several months). In consequence, the time axis of the graph can represent a few minutes as in the TV show example, or several months or even years (as in the elderly people example).

Now, let’s think about consumer decision making and see how this can be applied there. Marketing can be conceived as an endeavor to encourage people’s exploratory tendencies. Marketers want to pull people towards their products and services, and if we think about the market as a whole and think about it as a playing field of actors fighting for consumers attention, the idea that marketing stimulates exploration seems plausible. Let me delve into this thought for a little while. Check the following video about the process behind the marketing of a movie:

Two points from the video that I’d like to highlight are (i) the big budget marketing a movie requires and (ii) the closely related fact that many of the movies we end up seeing are produced by powerful studios. These facts have the consequence that many low-budget, independent, movies never get to gain the recognition that they might deserve; they remain hidden, as they are not able to afford the price of visibility. I think this is true of many products, not just of movies. Just to mention another example, in one of her posts, blogger Rosie Leizrowice remarks that, in order to escape the mainstream books, she used to go to random bookstores and pick whatever book she happened to lay her eyes on. In a more general tone, examples such as these show that some valuable products would be financially incapable of claiming a spot in consumers’ so-called “evoked set” (the products or services someone is aware of and which, in consequence, exhaust the alternatives people would consider consuming). Marketing then not only constitutes a field where exploration is encouraged but one where it is limited to a certain set of alternatives. Some people, like Rosie Leizrowice, worried by a fact such as this, are bold enough to just erratically buy something they have never heard about -a strategy that, from time to time, in a world where your view of something valuable could be obstructed by money, is more than justified.

There is another conception of marketing that puts it in stark contrast to people’s exploratory nature. Most marketers nowadays focus on creating not single interactions but long-term relationships with customers. Many businesses are willing to sacrifice gains in the short-term and trade it for long-term profitability, making use of marketing approaches whose goal is to take full advantage of the lifetime value of a customer (the value a customer can have for a company over many years of interactions with her/him). This is one of the reasons loyalty programs have exploded over the last years, with almost any kind of business rewarding customers’ loyalty, from supermarkets to airlines to fast-food restaurants to nail salons. A way of reading loyalty programs in relation to the explore/exploit dilemma is as an exploration penalty, one that is, by the way, very tangible: money. Let’s go back to the example of the restaurant to highlight the consequences of this. You have frequented a restaurant for quite some time (let’s call it Food Station) and, as a result of this, you have been getting some free meals: one per every fifteenth time you have visited. You have already claimed a bunch of these. Food Station serves good food and, as a business, it “wants” to transact with its customers as much as it can. Food Station is not at all eager to see you choose Food Stop (one of its competitors) to have one of your meals so, of course, as soon as it has the chance to reward you for eating there, it does. The Food Station reward is simultaneously a penalty. If you try Food Stop you would be given up the possibility of adding one more visit to your scorecard for a free meal in Food Station. In this scenario, which is common in today’s markets, exploration not only comes with its inherent uncertainty but with the certainty that you are probably losing something on top of the exploitation itself of the knowledge you have gained in the past. However, once again, it seems that exploration, under the right time constraints, is worth it. The reason is that loyalty rewards seem to cancel each other out. Food Stop does surely have a loyalty program too, so it’s worth it to find out if you happen to run into your new favorite meal there -don’t let penalties fool you.

I have personally found loyalty programs much less exploration-threatening than YouTube recommended music videos. As you likely know, YouTube’s algorithm personalizes its content to the user. This essentially means that YouTube is very good at keeping its users clicking on the next video. And with music, that video is probably a song you like and that you have heard tons of times. I was thinking about why I keep clicking on music I like and don’t invest more time searching for music I might like. My answer was that I do not know how to search for music and this kind of makes sense in other domains. If you don’t know how to go about exploring, you’ll likely stick to the safe, known, options. But the internet has a roadmap for pretty much everything. A google search spat this nice website out: 8tracks. So, go do some exploring, young fella!